The Ladies of Alton

This part of Alton's footbridge history has tended to be a footnote in the overall history, when in reality it is what saved it for posterity. Some of the wording on this page originally featured on the main footbridge history page, but the quantity of information now justifies a page in its own right.

As the footbridge history page explains, the footbridge at Alton station was originally an open design. It was quite normal for footbridges to be unroofed and they continued to be installed in that form in many places until the 1990s. The open design was not popular with "the ladies of Alton", so they successfully lobbied the London and South Western Railway (LSWR) to have the bridge roofed and the lattice sides boarded over (internally) in 1894. Clearly they were not satisfied with this because the bridge was fully enclosed with windows in 1896 and this is more or less the form we see today. These changes are recorded on the original plans for the footbridge that remain in the Network Rail archive - copies can now be bought from their media website.

The "Ladies of Alton" in the Alton Gazette

Until recently, the ladies of Alton story was anecdotal, although a number of railway books referred to them. In November 2016 Local historian Jane Hurst looked back through the old newspapers on microfiche and found the missing evidence. There were two letters published in the Alton Gazette in March 1894 that record the event:

March 9th: The Footbridge at the Railway Station:-

"The Directors of the London and South Western Railway Company through their general manager, Mr Chas Scotter, have been petitioned by the ladies of Alton to erect a covering over the bridge at the Railway Station. It is to be hoped that success will attend the request of the petitioners, as passengers at present are uncomfortably exposed to the inclemency of the weather while going over this bridge, in a way they are quite justified in resenting."

March 16th: The Footbridge at the Railway Station:-

"We are pleased in being able to inform our readers that the efforts of the ladies who have petitioned the L & S W Railway directors respecting this bridge, as recorded in these columns last week, are destined to be crowned with success; the following letter having been received by Mrs Wickham, that lady having kindly allowed us to give it publication.

'L & S W Railway, Secretary’s Office, Waterloo, London, 23rd February, 1894

Madam- The Chairman desires me to inform you, in reply to your letter of the 20th inst., that the Company’s Engineer is about to be instructed to improve the footbridge at Alton Station in a manner that will be found satisfactory.

I am, yours truly, W J Macaulay, Secretary.'

Mrs S E Wickham, Binsted-Wyck, Alton, Hants."

Jane Hurst adds: "Mrs Wickham was Sophia Emma Wickham (née Shaw Lefevre) 1833 - 1929 , wife of William Wickham (1831-1897) of Binsted Wyck near Alton. William was a Member of Parliament for Petersfield and a High Sheriff of Hampshire and they were important members of the community."

The photo above of Sophia Emma Wickham is held by the Hampshire Records Office (record 153M85/1/31) and is dated c1860. She died in 1929 at the age of 95, so lived to witness the passing of the 'Representation of the People Act 1918', giving property-owning women over 30 the vote, as well as the 'Equal Franchise Act 1928' where all men and women over the age of 21 were conferred the right to vote.

Suffrance Connection

This story of the "ladies of Alton" lobbying the railway company was an interesting episode in the history of the footbridge. Although we were linking it to the sufferance movement, but we had no hard evidence to prove this aspect. By chance, we came upon a website "Women and her Sphere" that contains a blog entry made by researcher Anthony Brunning. He tells us that he was doing research at the Hampshire Record Office in Winchester, and was looking through the archive deposited by the Wickham family. It included a petition booklet dated 1894 with the names of 32 women in the Alton suffrance group who signed the petition. This was a national petition that 50,000 women eventually signed. Most of these booklets were lost, but Mrs Wickham asked for hers to be returned. It contains some familiar surnames: Wickham, Hall, Trimmer, Osborn, Dyer, Chalcraft.

According to the UK Parliament page devoted to this petition, all these booklets from women's sufferance groups around the country were intended to be submitted with the 1894 Registration Bill. In the end, this bill was not put to parliament, so the petitions were submitted two years later to go with Mr Faithfull Begg’s Parliamentary Franchise (Extension to Women) Bill of 1896. All the petitions were laid out on tables, extending to a length of 50ft (15m), in Westminster Hall (part of the Houses of Parliament) for viewing. Despite all this effort, the bill was never discussed in parliament. Not surprisingly, women in the sufferance groups were outraged by this snub and it galvanised many women into doing more to get their cause heard.

In 1897, the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was formed, with Millicent Fawcett elected as its president. This was a peaceable organisation, attempting to elicit change through parliamentary legislative means. Others were not so patient, forming a militant organisation called the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) with the famed Emmeline Pankhurst at its head. The members of the WSPU became known as the Suffragettes, but were not wholly welcomed by those trying to gain parliamentary support for women's votes. A truce between the two suffrage organisations was agreed in 1910 whilst the Conciliation Bill was being prepared for parliament, but after two years of wrangling, the bill was defeated.

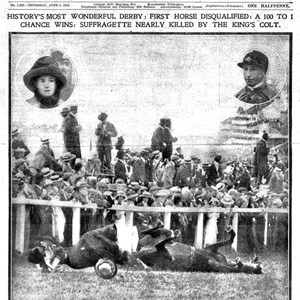

The Suffragettes (WSPU) were already unhappy with the watered-down proposals of the Conciliation Bill, and its failure to pass into law led to a stepped-up programme of militancy. Shop windows were smashed and there were arson attacks, leading to Suffragettes being imprisoned for their cause. Many went on hunger strike whilst in prison, including Emmeline Pankhurst, and were force-fed. Perhaps the most famous act of Suffragette militancy was the death of Emily Davison, trampled by the king's race horse at the Epsom Derby in 1913. At the time, many people saw this as an annoyance, drawing very little sympathy for women's rights.

The press were quick to say that Emily Davison was the first martyr for the Suffragettes. The event was captured on a 'Topical' newsreel film of the races and can be watched on a British Film Institute (BFI) YouTube video. Although history continued to record Emily Davison's death as suicide, there is evidence that she had a return train ticket and plans for other engagements in subsequent days, so there were doubts. In 2013 Claire Balding presented a Channel 4 programme called 'Secrets of a Suffragette' to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the event, and the programme-makers decided to have the contemporary film examined by experts. They concluded that she was trying to put a 'Votes for Women' Suffragette sash over the head of the King's horse (Anmer), but misjudged the speed that horses run. You can watch the programme on YouTube.

All political and militant efforts for women's suffrage ended with the outbreak of the first world war, but the issue did not go away. The Representation of the People Act 1918 was the first step in the right direction, but it didn't give all women the vote. It wasn't until the Equal Franchise Act 1928 was enacted that electoral equality was established, giving everyone over the age of 21 the vote. It is worth noting that the voting age was only lowered to 18 in 1969, and there are some now who believe it should be further lowered to 16. But that's another story...

Returning to the petition signed by the 32 ladies of Alton, the 1894 date is specific to their parallel efforts to get the Alton footbridge covered. Their success effectively preserved the fabric of the footbridge, so we owe them a debt of gratitude. Fate also played its hand. All the other similar wooden footbridges across the UK were either replaced or removed in the 1930s, but ours was not - the reason is not known. It would be a crying shame if the footbridge were to succumb now, having survived all these years intact.

Petitions continue to wield power for the people

The final message coming down the ages is that whilst parliamentary petitions have limited usefulness in lobbying parliament, external petitions are now taking democracy to the people. There are a number of petition-based websites and they are having significant influence on parliament and cabinet decisions. Whilst many MPs probably secretly dislike the interference from voters, publicly they are unable to ignore the numbers of people who sign these petitions. Most of these petitions are targeted at specific issues and often at very short notice, generating hundreds of thousands of signatures. Unlike the MPs in 1896, they do now sit up and take notice. Comments have been heard about MPs who are devising ways to ignore these petitions, but they are now caught in a new wave of politicised people who feel disenfranchised and underrepresented by the current parliamentary system. It is easy to think that the suffrage movement is confined to history, but it is clear that even today, people feel that the current system needs to change in order to be more inclusive and representative of all people.

Find out more about the history surrounding Alton's railways on the following pages:

HISTORY Page Index

Introduction: The Railway Comes to Alton

Footbridge History

The Ladies of Alton

Mid-Hants Railway

Basingstoke & Alton Light Railway

Meon Valley Railway

Longmoor Military Railway

Bentley & Bordon Light Railway

Click on these links, or use the drop-down menu above to navigate between the pages.